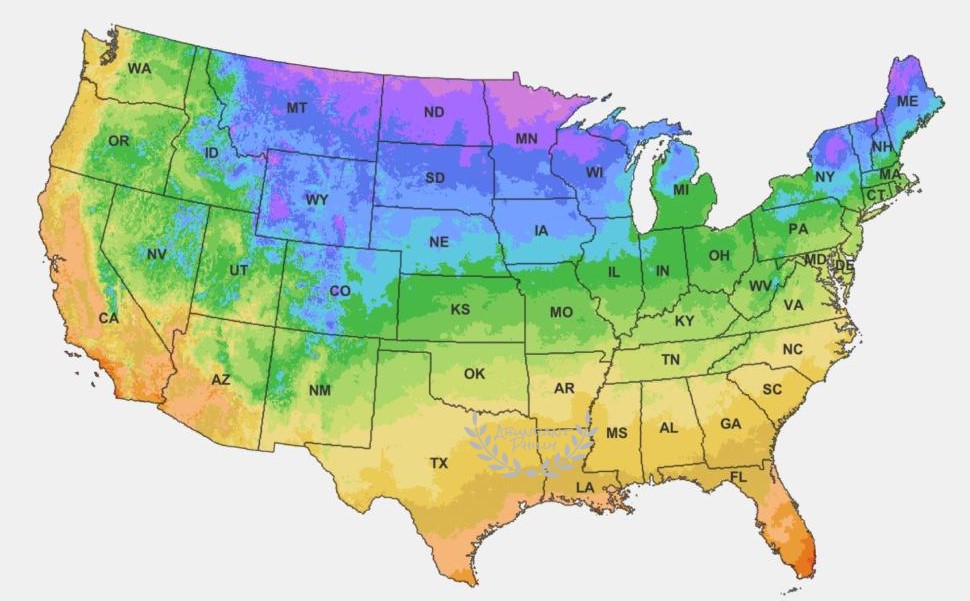

For the first time in 10 years, the USDA issued an update to its plant hardiness zone (more commonly referred to as growing zone) map for the U.S. This was both exciting, and ultimately anti-climactic, for us here in Philadelphia.

Let me explain why: This update comes from the increase in specificity to modern climate tracking – the USDA now relies on nearly twice as many weather stations across the country as they had previously – and this improved tracking has led to much of the northern half of the country moving into a warmer growing zone. A warmer zone could potentially mean a larger selection of plants that would survive as perennials in the garden. We are just ONE ZONE AWAY in Philadelphia from being able to grow citrus trees outdoors year-round, for example!

And yet, Philadelphia was spared from any such generous update to our zone. We remain in a zone 7B designation. Cue the sad trombone for this Florida-born transplant!

Nevertheless, it’s important to for all growers in the U.S. understand what their growing zone means for gardening and farming practices.

Why Pay Attention To Your Growing Zone?

The growing zone you’re in is based on the estimated lowest temperatures you’ll reach during an average winter in your area. Here in Philadelphia, as a zone 7B growing zone, that means on average our winters can get temperatures as low as 5-degrees Fahrenheit. The colder the average winter, the lower that area’s zone number.

This information is incredibly important for selecting which perennial plants (including edible plants, like fruit trees or berry bushes) will safely withstand your area’s winters. As I mentioned earlier, most citrus, while there are a few exceptions to experiment with, will grow in zones as low as 8 and as high as 11. For those who live in tropical, subtropical or even simply warmer temperate environments, growing zones also help to determine which perennial plants would not last in their area due to that plant’s need for chilling hours (i.e., amount of time spent in below-freezing temperatures.) For example, growers from my hometown in SW Florida, zone 10b, would struggle to grow sweet cherries, which thrive in zones 9-5.

For us growers here up north, knowing our growing zone can also help guide how protective we’d need to be with season-extension tools if we hope to “push our zone” and grow things that would need protecting from the lowest of our temperatures.

For example, it is commonly understood that a single layer of greenhouse plastic over top a garden bed with hoops, can boost the growing zone by one number, turning a zone 7 environment into a zone 8 environment.

This is an additive effect – so two layers of plastic would turn a zone 7 growing environment into something closer to zone 9.

Growing Zones vs. Frost Dates

Just a quick note to reflect that a growing zone is not the only important characteristic of the garden’s environment to consider, especially as we approach the start of Spring. The estimated last frost date at the beginning of the growing season and the estimated first frost date at the end of the growing season also have an important part to play in garden planning and planting.

The last frost date is an estimate for when in the Spring you can expect temperatures to remain above 32-degrees F. This is helpful for planning when to plant out frost-tender annuals, like tomatoes or cucumbers, which suffer when the weather is too cold. You can also work back from this date to time when to start seeds indoors. Of course, if you’re deploying the winter-sowing method for starting seeds outdoors before Spring, this becomes less important.

For us in Philadelphia, our last frost date is usually mid-to-late April.

And conversely, the first frost date of the season is an estimate for when in the Fall/early Winter you can expect temperatures to start to plummet below 32-degrees F. At these cold temperatures, you can expect the growth of most edible plants to slow down, if not stop all together. So, if you’re trying to grow vegetables to harvest fresh at their mature size come Thanksgiving or throughout the winter (which is possible in Philly! A future post will explore my experiences with it), its handy to know how early into the Summer or Fall you’ll need to sow those seeds or plant that transplant.

For us in Philadelphia, our first frost date is usually mid-to-late October.

I’ll note that these dates are estimations based off the historic weather patterns for an area. They change every year. And they are not always correct – its critical that you start watching the 10-day weather forecast as the weather warms (or cools!) to help guide precisely when you should execute your plans. Nighttime temperatures often matter more than daytime (plants do most of their growing at night!) But for those dreaming of Spring, the Farmer’s Almanac is a fantastic resource for figuring out what those estimated frost dates are for the year ahead.

I have a few more thoughts on how the unique characteristics of city-living in Philly make navigating our frost dates a bit tricky, but I’ll save that for a future post.

Pushing The Zone With Unusual Varieties

For us northern growers, we will often grow edible crops as annuals that would otherwise grow as perennial in warmer environments – peppers are a great example. While one can certainly get away with overwintering a pepper plant by moving it indoors during winter, the truism remains that pepper plants will not survive a Philadelphia winter outside due to our 7b growing zone.

The absolute beauty of nature, however, lies in its diversity. I’ll be growing a pepper plant this year that can withstand temperatures as low as 5-degrees F, Capsicum Flexuosum. These plants can live 30+ years and offer small, sweet, spicy fruits. I’ll do a fuller variety review after this first season. And with this past winter so far not dipping below the 20’s in temperature, I’m cautiously optimistic I’ll have a perennial source for sweet pepper jellies, sauces and chili flakes for years to come! I’d encourage anyone to seek out those convention-defying varieties and give them a shot where you live.

Stay growing,

Key